I'm plagiarising myself here: this is the text of a review I wrote a couple of years ago when Catnip reissued The Magic Pony. I don't think I can usefully say anything more than I said then. This is a fantastic book.

#

Patricia Leitch’s books are immensely satisfying; multi-layered: they succeed on so many levels. If you want to read

The Magic Pony as a pony adventure in which a girl rescues a woman from dying somewhere she didn't want to; rescues a mistreated pony from appalling conditions, and sees her own horse recover from a mystery foot injury, it works perfectly on that level. As a pony story, it is extraordinarily good, but it has much to say on ageing, and on death, and on how we perceive those around us.

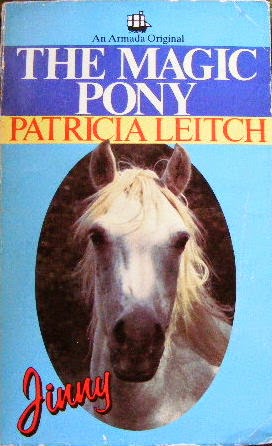

|

| Armada 1st edition, 1982 |

The Magic Pony is the seventh in the Jinny series. Jinny is struggling with school (the intractability of algebra), and the utter frustration of a half term that has seen even she, normally uncaring about the weather, restricted to home in the face of the deluge that lasted until the last day of half term. And now the last day has come; it has dawned fine, but Jinny has to go to the dentist, and finish her algebra. When at last she is free, she rides Shantih into the dusk, but in a fit of fury at the things that restrict her; family, school, she hurtles with Shantih towards a high stone wall. Shantih crashes on the other side, and is lamed. Nothing Jinny or the vet try, over the coming weeks, seems to work.

|

| Armada, 1985 |

In a search for a horsey expert who will be able to divine the cause of Shantih’s lameness, Jinny tries a nearby riding school. It is a hell-hole, with half-starved horses, overworked and uncared for. Amongst them is Easter, an ancient grey pony in whom Jinny can still see the remnants of beauty. Jinny is determined to rescue Easter. Over-reaching all of this is Kezia, the Tinker woman, who has been taken into hospital to die. She wants to die as she lived, in the hills, within reach of the outside, but she needs Jinny’s help to do it. Jinny is uniquely placed amongst those Kezia knows: a child outside the traveller society, she will be able to marshal the right sort of help.

|

| Severn House, hb, 1986 |

Death is not the normal preserve of a pony book; not the death of another human being, at any rate. Neither is age. It struck me when reading the book that sadly, little has changed since the book was written in 1982. When she learns that Kezia is dying, and wants to see her, Jinny’s first reaction is horror: in her life “people were either alive or else you heard they’d died. You didn't visit them, knowing they were dying.” The dying are tidied away, neatly, in hospital. That is where all right-thinking people believe they should be, and Jinny at first unthinkingly parrots this line. She comes, though, to recognise that the right-thinking way is not necessarily the way for everybody, and she, and those adults she knows will be sympathetic, help Kezia to sign herself out of the hospital.

The unexpected help too. This is one place where Patricia Leitch is so clever: we typecast people, and expect them to react in certain ways. Mr Mackenzie, owner of the farm next door to Finmory, is never slow to point Jinny’s stupidity out to her. He is the bastion of good sense, and has little time for her flights of fancy. But Kezia has asked to die in Mr Mackenzie’s bothy, and Jinny asks him, and he says yes. Kezia was a “bold one” in her youth, says Mr Mackenzie, a beauty. “It’s the sleepless nights I've spent tossing on my bed thinking of that one. Aye, So it is.” Jinny hurries away, not wanting to know. It is difficult to see the old; the middle aged even, and to think that they were once as you are now.

|

| Armada, 1992 |

The old women in Kezia’s ward “the parchment skins, gaping mouths and white wisps of hair,” remind Jinny of the awfulness of the riding school, where she felt “the same hopelessness, the same empty endurance.” The pony Easter “is like a ghost – so old she seemed hardly there, unable to stand against the assault of the light.” And yet Jinny is able to see, every now and then, what lies within both Kezia and Easter. The outer shell does not matter: there is still fire within.

“She looked up out of the window again. Keziah was tall and stately, the robes she wore about her shoulders trailed to the ground. She rode a white mare, proud-stepping with eye imperial and cascading mane and tail. A handmaiden walked by her side, and a page boy walked at the head of her palfrey. All the fairytales Jinny had ever read, all the illustrations she had ever seen of queens upon white horses, or wise women, or elfin lands, took hands and danced in Jinny’s sight. She watched spellbound.

For a minute they dropped out of sight as the track looped downhill and when they reappeared the spell was broken.”

It is not just the skins of the aged Jinny, and we, need to learn to see beneath. There is Miss Tuke, the generally dismissive owner of the local trekking centre, who sets about the owner of the pathetic riding school. Brenda, who runs the riding school, once had dreams herself, but has been utterly ground down by life.

“For a moment before Brenda turned away she smiled at Jinny, her mask drawn back, and, for a second, Jinny saw quite clearly the girl who had once shared her dreams.”

When Kezia’s death comes, Patricia Leitch meets it head on. There is no “passing away”, or even the dreadful modern “passing” (passing away-light? Is one only half dead?).

“Easter came slowly towards them. She reached out her head and breathed over Jinny’s tear-stained face, exchanged curious questioning breath with Shantih, then stood waiting.

‘Keziah’s dead,” said Jinny bleakly. She’s gone. No more. Dead.’

This is a brilliant book; in which every time I read it, I see different things. There is Jinny herself, meeting life head on; flawed and intolerant but fighting her way towards understanding the world and how it works; “the right thing to do.” There is the glorious mixture of myth and faith: the Red Horse, personification of the horse goddess Epona, and the unspoken communication between human and horse.

It’s the sort of book that pierces you with the beauty of its language. Jinny’s “great camel groan” when she has to get back to her algebra and not ride Shantih, is the sort of thing that resonates over the page to anyone who has had to turn away from what they really want to do and get on with the dull, the oppressive, and the everyday. And the horse, the wonderful Shantih. There are few, if any, pony writers better than Patricia Leitch at capturing the blazing brilliance of the Arab. Shantih, cured by Kezia’s herbs is restored and vital again.

“Jinny felt her drop behind the bit, her weight sink back on her hindlegs as she reared, struck out with her forefeet, then with an enormous bound was galloping up the track to the moor.

Shantih was all captured things flying free, was spirit loosened from flesh, was bird again in her own element.”

|

| Catnip, 2012, pb |

~ 0 ~

The Magic Pony was published as an Armada original in 1982. Armada reissued it twice after that, with new cover styles, in 1985 and 1992. Severn House released a hardback version in 1986, and that was the last single volume appearance until Catnip reissued the book in 2012.

The Magic Pony has also appeared in compilation form in

Three Great Jinny Stories in 1995, bundled together with

Horse in a Million and

Ride Like the Wind.

Comments