Horse Tales - Cambridge Conference May 2016

I'll report later on what actually happened at the conference, but in the meantime, here is the text of what I said. This is the full version, because reading this lot out would have taken considerably longer than I was allowed so drastic pruning took place before the event. [Edited to add this is in a large part my fault. I know how many words you need for five minutes, but was sort of hoping I could speak quickly and it would all be ok. Alas the stopwatch was not my friend, even with my million-mile-an-hour delivery, so cut it was.]

The adult world

As well as the fantasy element, one attraction of much children’s literature lies in the fact that it puts the child in an adult situation, but one that’s copable-with. Enid Blyton’s Famous Five had adventures on their own in the holidays, but Uncle Quentin was nearby, and real life always rolled back around again with the end of the school holidays.

Reality, of a sort

With pony stories, life is not like that. Day in, day out, year in, year out, the pony needs looking after, and certainly in the vast majority of pony books, the person in sole charge of the animal’s welfare is a child. In the Jill books, Jill, once she’d learned the ropes, had complete and utter say over what happened to Black Boy and Rapide.

Freedom

Perhaps in a world where children are less and less likely to experience the world on their own terms; where the chance of a child having the opportunity to experience adventure out in the wilds, on their own apart from their ponies is vanishingly rare, the pony has come to represent something sadly tantalising to the modern child, and something their predecessors took for granted: freedom. Freedom to act as an adult; freedom to perhaps hack out and be alone and unsupervised.

***

I approach the pony book now from a similar perspective to many children today. I live in a world that is relatively horse-free. I no longer ride. I now live in the middle of a town, where the closest I get to a horse is the carved relief of a horse opposite our local Marks and Spencers.

The 1920s–1930s

That is not how the world was when the pony book as we know it was developing. In the 1920s and 1930s, the position of the horse was massively different to what it is today. It was entirely normal for horses and carts to be seen around the streets. Horses took goods from railway stations in huge numbers. In 1937, the London, Midland and Scottish Railway Company was the biggest private owner of horses in Great Britain. Its stables contained nearly 8,500 horses, with 2,000 in London alone. There were horses everywhere: there were horse hospitals in Camden and Willesden, huge railway stables in several London locations, and in many other cities. The clip below was filmed at the Camden stables in London in 1949. It was indeed another world.

The 1920s–1930s

That is not how the world was when the pony book as we know it was developing. In the 1920s and 1930s, the position of the horse was massively different to what it is today. It was entirely normal for horses and carts to be seen around the streets. Horses took goods from railway stations in huge numbers. In 1937, the London, Midland and Scottish Railway Company was the biggest private owner of horses in Great Britain. Its stables contained nearly 8,500 horses, with 2,000 in London alone. There were horses everywhere: there were horse hospitals in Camden and Willesden, huge railway stables in several London locations, and in many other cities. The clip below was filmed at the Camden stables in London in 1949. It was indeed another world.

As well as working horses, there was much easier access to riding horses. There were riding schools in the middle of towns. The Cadogan Riding School, which was in Central London, had 250 horses at the outbreak of war in 1939, and it was by no means the only riding school in London. Thousands of horses worked on farms.

But change was coming. I can remember the immense thrill as a small child in the 1960s of the coal cart coming round, being pulled by a horse. It was exciting precisely because of its rarity. Almost all ferrying of goods by the 1960s was now done by vans and lorries. Horses were sold off from farms in huge numbers in the 1950s and 1960s as mechanisation took over. My family farmed, but the horses were long gone by the time I came on the scene. When I was around 10, someone found an old horse collar in an outbuilding, green with age, and gave it to me, because they knew I liked horses.

And exposure to horses has continued to decrease. The inner city riding school is a rare beast. The horse has now been ‘tidied up’ into livery stables, often with segregated grazing. The scrub pony grazing on scrub land on the edges of towns is (perhaps thankfully) becoming more and more unusual.

And yet… even though most children rarely see an actual, live horse in their everyday lives, that seems to make no difference to their attraction to the horse and their desire to read about it. There still seems to be some strange, entrancing pull that the horse has for us. You can see it through the number of pony books published, which has recovered from its low point in the 1980s to levels that in the first decade of this century rivalled the pony book’s glory days in the 1950s. And pony books continue to be published in large numbers, aided by the rise in self-publishing.

The thing is, that if the horse bug bites you, it is not particular about where you live, or how likely it is that you are going to be able to do anything about it. For many pony book readers, reading a pony book is the closest they are ever going to get.

I can remember one of my nieces, who had led a totally pony-free life, saying when we arrived for Christmas, ‘When you were on your way up through the garden, did you happen to see a pony? Because I did ask for a pony for Christmas?’ Sadly, the garden was completely and utterly pony-free, and I did sympathise because my own present lists had always included a pony, and this is the nearest I got:

A fantasy landscape?

I would argue that the ability to experience a real-life horse, whether that is simply seeing it go by in the street, makes no difference to how much children want to read about horses and ponies. Whether that’s because horses and ponies are part of the fantasy landscape of the inner child, and are in fact similar to the wizarding of Harry Potter, is unclear. The relevance of their everyday lives to ponies, and their chances of riding themselves also seem to make no difference.

The adult world

As well as the fantasy element, one attraction of much children’s literature lies in the fact that it puts the child in an adult situation, but one that’s copable-with. Enid Blyton’s Famous Five had adventures on their own in the holidays, but Uncle Quentin was nearby, and real life always rolled back around again with the end of the school holidays.

Reality, of a sort

With pony stories, life is not like that. Day in, day out, year in, year out, the pony needs looking after, and certainly in the vast majority of pony books, the person in sole charge of the animal’s welfare is a child. In the Jill books, Jill, once she’d learned the ropes, had complete and utter say over what happened to Black Boy and Rapide.

Mrs Darcy, the owner of the riding school, was there for expert advice if needed, but Jill and her friends were expert enough to help with the running of the school when Mrs Darcy was away (something of a trope in pony literature – there are many noble pony book children who have taken on the running of a riding school when the owner was ill.)

And they have real-life parallels. The Pullein-Thompson sisters started their riding school in Oxfordshire when they were all in their mid-teens.

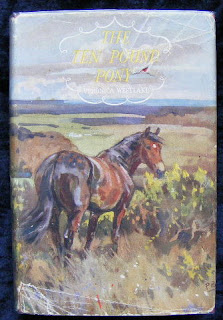

Economic reality is perhaps one of the things that divides most children’s literature from the real world. Parents and guardians are (almost) always there to pay for things and make sure every day life continues. The reality of owning a pony pre-supposes that you do actually have a certain level of family income: that you live somewhere where pony owning is possible, and that whoever looks after you can cover the expenses of everyday life. Nevertheless, there are many examples in pony books of children having to face some of the economic reality of horse-owning on their own, whether it’s Jinny selling her paintings to keep Shantih going, or the family in Veronica Westlake’s The Ten Pound Pony earning every penny of the pony’s purchase price, and its keep, themselves.

Freedom

Perhaps in a world where children are less and less likely to experience the world on their own terms; where the chance of a child having the opportunity to experience adventure out in the wilds, on their own apart from their ponies is vanishingly rare, the pony has come to represent something sadly tantalising to the modern child, and something their predecessors took for granted: freedom. Freedom to act as an adult; freedom to perhaps hack out and be alone and unsupervised.

***

I've now finished pieces on the rest of the conference:

Comments

Well done, it is amazing indeed how that love of horses appears so spontaneously, it seems. I've always wondered about the world outside of the English-Irish-American-Australian sphere...do German girls go "Pferd-verruckt"? (spelling is surely wrong there...). Are ponies popular among girls in France, Spain and beyond into Eurasia? (I know South and Central America have strong equine traditions, but not sure how girls play a role in that. Seems fairly macho in cultural history there.)

In fairness to the organisers, I'm sure if I'd suggested something suitable for a talk they'd have considered it! But I didn't. Partly I think because my mind was full of other horsy stuff. I have now had an idea for a talk (bit late, but there you go), which is war and the effect it has on pony books and whether that's any different to children's literature as a whole.

Elaine. Good points. It'd be interesting to know if anyone's done a study on exposure to animals and their effect on mental health. I'm sure they have - I know there are studies saying that exposure to animals is good for your physical health because of exposure to all those lovely germs.