Controversy: Riding Magazine and equestrian controversy in the 1940s

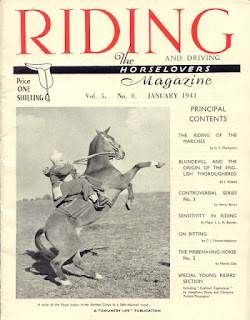

On my Facebook page a few weeks back, I posted a cover of Riding Magazine from 1941,

really because it was the Pullein-Thompsons’ first appearance in print

(Cocktail Capitulates – a piece written by all three on the schooling of a

difficult pony). The whole point of a front cover is to encourage people to

dive into the delights contained within, and as the magical pull of this

edition had not faded over the 70 plus years since it was published, people

wanted to know what was the controversy mentioned on the front cover?

|

| Riding, January 1941 |

The controversial horse was a series of articles appearing

each month on a topical controversy. I’ve found three so far, and when I’ve

found the rest of my 1941 copies, I shall be able to tell you if they continued

beyond that. The series kicked off a couple of months before the issue above, with an article on how best to control the horse.

If you fought off the temptation to go straight to the article

in November 1940’s issue, The Mental

Aspect of Control – Ascendancy of the Human Mind by Rufus, but read the

editor’s Notes of the Month, you would have been left in no doubt about the

editor’s opinion on controversy number one. ‘The author, it would seem,’ wrote

RS Summerhays, somewhat disingenuously as presumably he had had at least

something to do with the commissioning of the article, ‘is against physical

correction and would rely entirely upon mental control … he looks upon the

association between man and horse as a battle of brains devoid of the element

of physical contest, adding, in effect, that if it comes to the latter, it is a

case of pitting strength against strength to the rider’s disadvantage. We think, however, that is where the argument lies. Does the

rider, in fact, come off worse?’

The editor then makes a comparison that I’m not entirely

sure stands up to rigorous examination, when he draws a parallel between the

author’s rejection of reprisals to the country’s current fight against the

Nazis:

The author is against reprisals

of any sort, a matter of great concern to us just now in more important matters

than the relationship existing between horse and man. We doubt the

effectiveness of mental persuasion on the Nazis.

Just because something’s true in one set of circumstances,

it does not mean that it is in another. But the editor left this fairly

colossal sideswipe as his last, and one would presume he thought, unanswerable,

word on the subject.

Rufus takes what is still a thoroughly topical debate – think

of the controversy about the use of the whip in racing, or the tremendous huhaOliver Townend found himself in when having over-used the whip on both his

Badminton horses – and questions how far one should go when using physical

methods to control the horse.

|

| Moyra Charlton – Three White Stockings |

Rufus, I strongly suspect, would not have approved at all of

Mr Townend, or the many examples you can see every day of riders using the

latest fashionable bit of equipment as the answer to all problems of equine

disobedience.

… invariably,’ he says, ‘we find

that far too much stress is laid on the practical side of the question, on this

or that bridle, on this or that method of holding the reins, and not nearly

enough attention is paid to what might be termed the mental aspect of control.

Using force against a horse which

disobeys is equivalent to kicking the electric light switch when the lights

have fused: it only makes matters worse.

Rather, says Rufus, you must use your brain when trying to

persuade your horse to do what you want: because in a straight trial of

strength, a human being will never win. He believes that ‘the horse never disobeys

out of “sheer spite” but over-freshness, bad riding or bad training.’ Rather

than spite, perhaps, I would allow some ponies I've met sheer bloody mindedness.

But for whatever reason your equine misbehaves, to overcome behaviour you do not want, you must play a sort

of game in which ‘we must know how to lose should the horse momentarily get the

better of us.’ Wise words.

Rufus believes that it is impossible to transform a horse

into a mere robot – the ‘rigid German school of horsemanship’ being the nearest

example he can think of, which he compares to the Italian school at the other

end of the spectrum, which aims to give ‘the maximum possible scope to the

horse’s individuality compatible with control.' I wonder what Rufus would make of equestrianism now, when the pendulum does seem, in some quarters at least, to have swung very much over to the German approach.

Rufus advises tact, and putting yourself in the horse's place. Rather than try what seems logical to you, think about what is logical to the horse you are riding. If you have a well-schooled but impetuous horse,

don’t start off by galloping round the field and then expecting the horse to

settle to schooling now that you have thoroughly worked it up. But if the same

horse frets at the back of the hunting field, let him go along in front for a while,

so that having temporarily given in you can get him back to what you want

through tact and guile.

|

| John Thorburn – Hildebrand |

I don't claim to be an expert rider (very, very far from) but the small riding success I have had is in trying to meet a horse at least half way. So, writing many decades later, I have to say I am pretty much

in agreement with ‘Rufus’. I find watching Badminton, and its ilk more and more

difficult as, whether for reasons of commercial imperative or sheer

competitiveness, the role of the horse as ‘a willing co-operator*’, as a

partner, is ignored by a small but definite percentage of riders. And in the

wider equestrian world, the latest gadget or practice, whether it be the flash

noseband, crank noseband, or rollkur is (mis)used to force the horse into

obedience.

***

* John Thorburn’s Hildebrand

(Country Life, 1930), is a fantasy about a horse who has ceased to be ‘a

willing co-operator’. As Hildebrand is also blessed with considerable brains

and the ability to talk, tact and guile (or possibly outright bribery) would be

the only ways to persuade him to even

consider doing what you would like him to do. You can read more about John Thorburn on my website.

Comments