The mark of a good exhibition is learning things, and being made to think about things you had previously not considered. I freely admit military history is not something I spend a lot of time over. Sharpe and all Bernard Cornwell's fighting creations I love, but the minutiae of military manoeuvring generally leaves me cold. In that all of it impacts on living creatures; human and animal, it shouldn't, but it does.

The War Horse exhibition is right up my street, being about the effects of war on skin and bone; equine skin and bone. A fair chunk of the exhibition is taken up with Michael Morpurgo

and

War Horse, the book, play and movie. That section of the exhibition is worth it if only to see the original of Victor Ambrus' illustration for the

first edition of war horse. The original cover wasn't helped by the overall cover design. The illustration on its own, framed (and now owned by Michael Morpurgo) is stunning.

The rest of the exhibition is well done. I had expected to come out of it with a broad sense of the part the horse played in war, and I did, but rather to my surprise, it was individual artefacts that made the most impression - the

farrier's axe, for one. It was the stern practicality of it that got me: horses die in war, as we all know, but they are also terribly injured. I had assumed that seriously injured horses were shot, but for most of humanity's history, the bullet didn't exist, so what happened to the horse then?

What was used to deal with the situation was a farrier's axe. This had a spike on one part of the head, used to put the horse out of its misery, and an axe on the other, used to take off a hoof. Each horse would have had a numbered hoof, and what had happened to each horse could therefore be recorded.

When I think of war, I tend to think of the death-or-glory moments, and certainly not the clearing up. All credit to the National Army Museum for including a section on the Brooke Hospital's work in Egypt. After, rather confusingly, stating that "The War Office promised that unwanted horses in Egypt and the Middle East were to be destroyed rather than sold on to cruel owners..." the next display talks about the miserable wrecks of army horses which Dorothy Brooke found when she moved to Egypt with her husband in 1930, without explaining how the horses got into that state, as they were obviously not destroyed.

When Dorothy Brooke found these horses, and there were thousands of them, not just a few, she organised an appeal through the Morning Post. It raised over £20,000 and the Brooke Hospital for Animals was born in Cairo. The

Brooke Hospital did, and does, amazing work. There are still many, many working horses in the world, and the Brooke is dedicated to improving their lot through veterinary treatment and community education. It is out of print now, but if you can find a copy of

For Love of Horses - Dorothy Brooke's Diaries, now sadly out of print, it is a fine read. She saw some truly terrible things. Most of the photographs following are not in the exhibition: some are graphic and upsetting, so please click away now if you are feeling fragile. The National Army Museum presumably has not included the worst lest they upset, but the end result of war for many horses was painful death, and for some unfortunates, years of suffering.

|

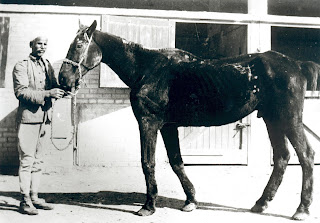

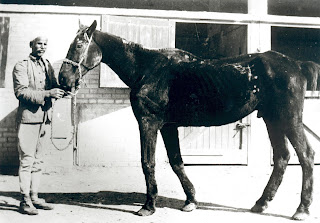

| Old Bill - one of the first war horses rescued by Dorothy Brooke in 1931. His photo featured in her original appeal to the Morning Post (now Daily Telegraph) in 1931. |

|

| Dorothy Brooke |

|

| One of the first horses rescued |

|

| An emaciated horse in Cairo |

|

Emaciated and suffering horse collapsed in a Cairo street

|

|

| One of the first horses rescued by Dorothy Brooke |

|

| Buying day |

|

| Dorothy Brooke in the yard of the SPCA in Cairo with some of the war horses she rescued |

I can highly recommend the rest of the museum. If military strategy is not your thing that does not matter. The exhibits are wide ranging, and I had a thoroughly fascinating couple of hours fossicking about in what were not quite deserted galleries, but certainly not brimming with visitors. This is sad, as the museum's focus is on humanity, not tactics. I'm not entirely sure which of those categories the skeleton of Napoleon's war horse, Marengo's, skeleton comes into, but that's there too.

Thank you very much to the Brooke Hospital for supplying me with photographs from their collection. All photographs © The Brooke

Comments

Sarah

A group of mules were transporting guns across some mountains. One mule (carrying a very heavy gun barrel) lost its footing and fell down a ravine. The farrier was sent down to put it down as they thought it would have been horribly injured.

Mule saw the farrier (and his axe) coming and, making a tremendous effort, got to its feet and back up the slope (still loaded down with the gun barrel) to join the others.

Mules are tough, and very clever!

Sue, I did love your story. There's a mule section in the exhibition, albeit a small one. It's about Jimson the mule, who actually won two medals!

One of the very best bits of War horse writing [for me, anyway] was written by a German soldier, ''All Quiet on the Western Front'' by Erich M. Remarque- he served, and wrote of a British bombardment on German horse transports- the writing is powerful, the scenes appall, and the description of the silent moonlight before the bombardment, and the aftermath is gruelling to read. I foind myself hating the perpetrators, the British who also loved horses, but had unleashed such carnage.

Mules are indeed tough and clever- and yes, I did once own the Brooke hospital book, a slim blue volume, which I charity shopped for someone else to read- how I regret that now!

Fortunately horses and mules are not routinely used in combat now- just ceremonial duties.

Best Wishes,

Catherine M